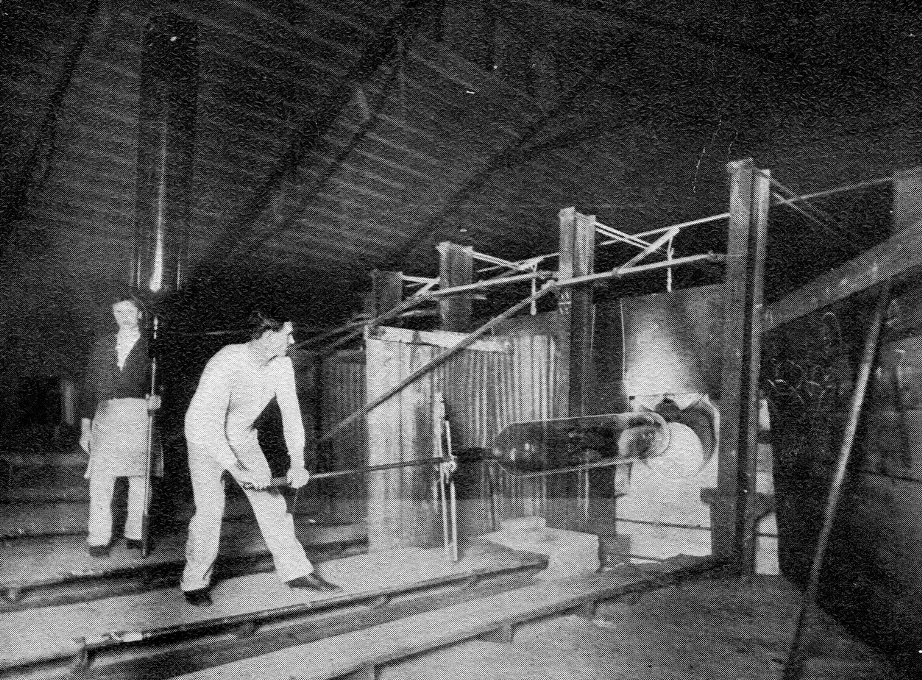

Photo from Life in Wellsboro 1880-1920 by Gale Largey

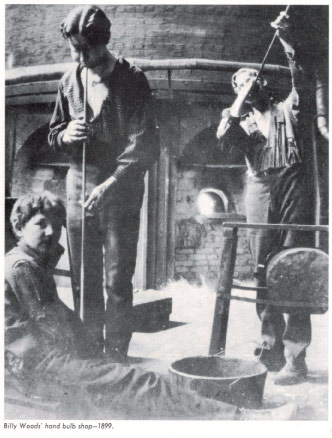

the ingenious Will woods

Will Woods returned to Corning before the plant expansion was finished. His success at Wellsboro was rewarded with a new position as the superintendent of the Corning Glass Works sprawling main plant. His new job didn’t keep him from thinking about bulb blowing machines. The company had recently installed an automatic tube drawing machine to replace the hand process used in both Corning and Wellsboro. The machine fed a ribbon of glass onto a rotating mandrel with air blown through the center and tubing was drawn off the end in a continuous process. In 1921, Woods formed an idea of how to use that ribbon of glass in a completely different way. According to his co-inventor, David Gray, Woods tested the idea by gathering some glass, flattening it, and laying it onto a metal plate with a hole in it. After letting it sag through the hole, he put the tip of a blowpipe that fit into the hole onto the glass and blew into it. He imagined a continuous chain of plates with a ribbon of glass on it along with blow heads on top and molds underneath. This idea would become the ribbon machine.

Gray was the engineer in charge of the Mechanical Development Department and worked with Woods to take his idea and turn it into a machine. Designing, assembling, and testing the 20,000 special parts for the machine took years and in 1924 they began assembling what was then known only as the “399 Machine.” They worked in secret in a corner of the factory that was strictly off-limits to anyone not on the project. By the following fall, they knew they had a machine that worked and had the perfect place to put it to use: the Wellsboro plant.