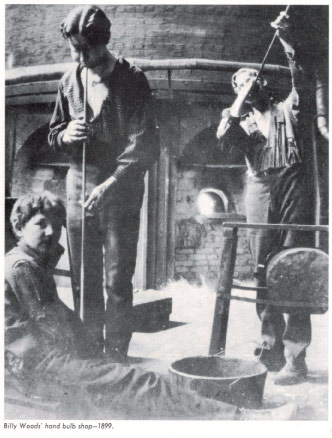

Photo from Life in Wellsboro 1880-1920 by Gale Largey

the ingenious billy woods

William J. “Billy” Woods was hired as the first plant manager for the new Corning Glass Works satellite location in Wellsboro in 1916. Billy quickly proved himself to be a hard worker and quick learner. In less than five years, the plant had expanded to include a second melting tank.

Billy Woods is seen here in the plant (in back, facing the camera) circa 1920 supervising the production of light bulbs on the semi-automated Empire or “E” machines. Twenty such machines were stationed around the tanks. These machines still required 3 workers each and plenty of manual labor to hand gather the glass and monitor the molds and bellows. There was one annealing oven for every two machines. Inspectors at this time were women.

The ever-observant and creative Woods was able to streamline operations and train his workers to maximize their efficiency until they were producing approximately 4,000 bulbs in each 8-hour shift. But Billy Woods was just getting started. He later invented the ribbon machine which revolutionized the glass blowing industry.